Part One: Home

My father would have truly been a gifted curator or gallery owner. He paid attention to every single detail and never let the dust accumulate on an surface. On good days, the house was quiet. We were never told that we couldn't be loud or that we couldn't run inside, as children we just picked up on the fact that we couldn't. Each object stood delicately with purpose and importance. Like a visitor getting too close to a painting or reaching out to impermissibly touch a sculpture, one could expect a guard to materialize from a corner of the room and politely ask us to leave.

Whenever I stayed over at my friends houses I was always struck by the fact that they were allowed to leave their belongings where ever they wanted. I envied their ability to arrive home, tired after school, and kick off their shoes and sling their backpacks onto the back of the dining room chairs. In my house, if you left anything that belonged to you anywhere but in your room my father would threaten to throw it away. Looking around our first floor, you wouldn't know that three children lived there. Our home was not organized around the needs of me or my siblings or even around the needs or wants of my parents. It was designed to look good to those people that came to visit and stay for a moment. Our furniture, the lighting, and everything else was stiff as a gallery. There was no place to wrap yourself up in a blanket and read a book, or space on the floor to lay with friends and watch movies. And so, as a family we could only find comfort in our rooms. Those spaces that our doors kept hidden from guests. While comfortable and safe it was also very lonely. While my father would have been a truly gifted curator, I would have to wonder what stories his exhibitions would tell. Unlike the Guggenheim in New York, this museum was not devoted to modern art. This museum did not celebrate colorful interpretations of landscapes or whimsical portraits like the Louvre in Paris. This museum was devoted to portraying the story of the family we wished we had.

When I consider the way that my father treated my home I realize how the pattern of putting community needs before individual needs was embedded in my mind. When I approach and issue or a task I do not consider what I want or even what I need. I think about what my students, friends and even my partners needs and adapt my solution to them. As a teacher, this explains whey special education accommodations always seemed like common sense.

Part Two: Table

There are two tables that present themselves in my mind when I considered what a table would look like. One was the table we ate dinner around as children and the other is my demonstration table in my classroom. Because I focussed around my family for the first part of this exercise, I wanted to expand my thought to include who I am today.

There are two tables that present themselves in my mind when I considered what a table would look like. One was the table we ate dinner around as children and the other is my demonstration table in my classroom. Because I focussed around my family for the first part of this exercise, I wanted to expand my thought to include who I am today.Most of the experiences that I have had around a table have been connected to either working, eating or socializing. In my mind when I think of a table, I think of laying out my photographs for my BFA show to figure out what order they should be presented in. I spent so much time teaching my students at my demonstration table or behind it as a drew or wrote on the board. Then I think of my work table at home and how many different functions it has had. It has been an area to clip flowers, to draw, to read, to eat and drink or simply to write. When I think of a table I feel like it serves one main purpose: to hold things.

My demonstration table is a unique space because everyone has a place. Unlike the table at Thanksgiving dinner, where only the adults got to sit, my students huddle around and watch in a circle. There is a place where a wheelchair can fit, so there really is spot for everyone. One thing that I do differently from my coworker who had the same exact table is that I have my students stand instead of bringing up their stools. I feel like they pay more attention to what I am doing and it also just gives them more breathing room. I feel like when there is a group gathered at any table, there comes a set of expectations. We keep our hands and our feet to ourselves, we give the head of the table respect and most of all we speak kindly to one another. At the demonstration table I am usually at the head, though I stand in the middle so I prefer to think of myself as the center. However, there are times where the table takes on a whole other purpose. It is often the surface that we spread out art work to dry if the pieces are too small for the drying rack. I place supplies and often instruct kids who find random things to "just set it on the demo table". While I like to think of it as a place of organization, it is often quite the opposite.

My demonstration table is a unique space because everyone has a place. Unlike the table at Thanksgiving dinner, where only the adults got to sit, my students huddle around and watch in a circle. There is a place where a wheelchair can fit, so there really is spot for everyone. One thing that I do differently from my coworker who had the same exact table is that I have my students stand instead of bringing up their stools. I feel like they pay more attention to what I am doing and it also just gives them more breathing room. I feel like when there is a group gathered at any table, there comes a set of expectations. We keep our hands and our feet to ourselves, we give the head of the table respect and most of all we speak kindly to one another. At the demonstration table I am usually at the head, though I stand in the middle so I prefer to think of myself as the center. However, there are times where the table takes on a whole other purpose. It is often the surface that we spread out art work to dry if the pieces are too small for the drying rack. I place supplies and often instruct kids who find random things to "just set it on the demo table". While I like to think of it as a place of organization, it is often quite the opposite.I think that age and social status are the largest factors when it comes to influencing the interactions with and at a table. If you are younger, you often have to ask permission to leave the table. As if it is not your choice to stay or leave. I realize that this is the same at the demonstration table. Even after telling my students that they do not need to ask to leave for music lessons or excel, they often will wait with their hand raised and ask me if it is okay if they go. My social status as someone who is older and identified as the authority figure by the students, allows me to be the one that makes that decision. I also believe that culture has a large influence on how we interact with table as well. I recently had a student who was new to the United States from the Congo. He did not know any english and his very first class of the day was art. One day, he got particularly frustrated because of the language barrier and simply picked up his supplies and put them on the floor. He squatted over his painting and began to sway back and forth and sing. I had no idea what he was saying but I could clearly see that he was far more comfortable than he was when he was sitting in a stool, painting at a table. This makes sense when you think about the African culture and the resources that they have access to. This students showed me how truly uniform I had my classroom set up. Each table was the same size, and same material while every chair was exactly the same stool. It made me wonder what it would look like to accommodate students not only for their academic success, but also their physical comfort.

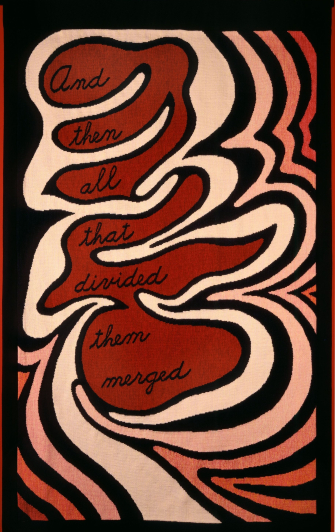

Up until this point I did not consider the shape of the tables I interacted with. After viewing the Judy Chicago video's and digital exhibition I realize now that they function as barriers. One person sits across from another almost in opposition. The only individuals that are free from this feature are those that sit at the head of the table. I was struck by the message that was stitched into the banners, welcoming visitors as they entered. It was only after reading the line,"...and then all that divided them merged..." did I realize that this is one of the main reasons why the table would be a triangle instead of a rectangle. The shape of the table not only unifies the women together but because it is open in the middle it also suggests that they are individuals. When I looked at the triangle again, I was also reminded of the alchemical symbols for the 4 elements that all reference a triangle. It reminded me that one element cannot exist on its own, but is only enriched by the presence of the others. I remembered then, one time that I attempted to change where I stood for demonstrations at my classrooms table. Instead of standing in the middle of the long side, I stood at the "head" of the table on the short side. I suddenly realized that I could see everyone more clearly, but I was overwhelmed by the feeling of "standing out" against my students. I never tried that again.

Up until this point I did not consider the shape of the tables I interacted with. After viewing the Judy Chicago video's and digital exhibition I realize now that they function as barriers. One person sits across from another almost in opposition. The only individuals that are free from this feature are those that sit at the head of the table. I was struck by the message that was stitched into the banners, welcoming visitors as they entered. It was only after reading the line,"...and then all that divided them merged..." did I realize that this is one of the main reasons why the table would be a triangle instead of a rectangle. The shape of the table not only unifies the women together but because it is open in the middle it also suggests that they are individuals. When I looked at the triangle again, I was also reminded of the alchemical symbols for the 4 elements that all reference a triangle. It reminded me that one element cannot exist on its own, but is only enriched by the presence of the others. I remembered then, one time that I attempted to change where I stood for demonstrations at my classrooms table. Instead of standing in the middle of the long side, I stood at the "head" of the table on the short side. I suddenly realized that I could see everyone more clearly, but I was overwhelmed by the feeling of "standing out" against my students. I never tried that again.

No comments:

Post a Comment